EUStudies@CBDS Held The #1 In-Europe Dialogue Discussing EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) and Its Impact on Indonesia-EU Relations

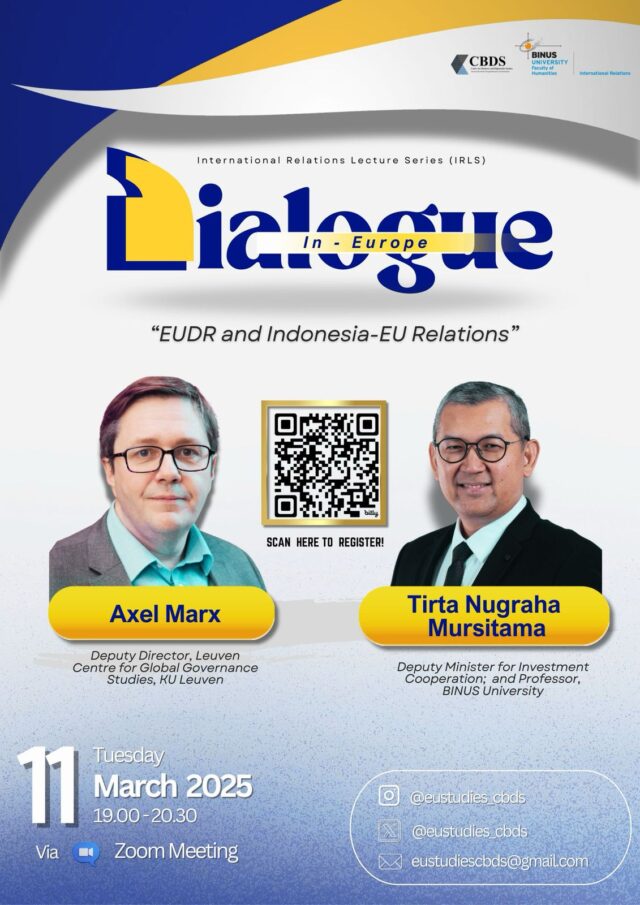

The first In-Europe Dialogue took place on March 11, 2025, offering an insightful discussion entitled “EUDR and Indonesia-EU Relations”. This discussion covers the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) and its implications for Indonesia-EU Relations. The discussion, organized by EUstudies@CBDS, serves as a platform for examining pressing issues within the EU-Indonesia relations framework.

Moderated by Sukmawani Bela Pertiwi, S.I.P., M.A, the session featured distinguished speakers. Axel Marx, Deputy Director of the Leuven Center for Global Studies at KU Leuven, and Tirta Nugraha Mursitama, Deputy Minister for Investment Cooperation and Professor at BINUS University. The discussion was attended by 88 students, lecturers, researchers and practitioners both from BINUS and other institutions.

In her opening remarks, Sukmawani Bela Pertiwi provided an introduction on the EU Deforestation Regulation as the latest contention in the relations between Indonesia and the EU. The Regulation aims to make sure products entering the European market do not contribute to deforestation by requiring traders and operators to provide due diligence statements. The products regulated in the EUDR include palm oil, cocoa, cattle, wood, rubber, soy, coffee, and some of their derived products such as leather, chocolate, tyres, or furniture. This created tension with Indonesia as the biggest palm oil producer in the world who sees this regulation as a kind of market protectionism. Given the relations between Indonesia and the EU which has been dominated by distrust and dispute, it is important to have dialogue from both perspectives on this issue in order to understand the drivers behind the EUDR and Indonesia’s position towards this regulation.

Axel Marx provided insights into the EU’s environmental objectives, emphasizing the regulation’s role in fostering sustainable trade practices. Axel Marx mentioned three contextual elements of the regulation. First, the primary objective of the regulation itself. The goal of EUDR is to prevent deforestation by regulating the trade of goods associated with forest degradation. This is in line with more general environmental initiatives such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the European Green Deal. The EU recognized that global deforestation was happening at an alarming rate, driven by illegal logging and agricultural expansion. The second context is the EU trade and external policy. For years, the EU has integrated sustainability into its trade policies. However, these methods have limits in its implementations when it comes to effectively halting deforestation, so the EUDR was created as a tougher mechanism to enhance sustainable trading practices. The third context is the existing sustainability efforts by companies. Many corporations have implemented voluntary environmental initiatives, such as “zero deforestation” pledges and certification programs. The EUDR expands on these efforts by making due diligence legally mandatory. This encourages more enterprises to comply with tighter sustainability requirements and creates more equitable markets.

Tirta Nugraha Mursitama, on the other hand, highlighted Indonesia’s stance, focusing on the potential economic disruptions and challenges posed by the policy to local farmers and businesses. Tirta highlights that Indonesia has previously adopted sustainability efforts such as the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) accreditation and the Timber Legality Assurance System (SLVK). These efforts are intended to promote sustainable activities while meeting international environmental standards. The EU does not fully recognize these efforts as it has its own structure and standards that poses a barrier to indonesia. The EU’s strategy does not fully account for local conditions, smallholder efforts, and Indonesia’s national sustainability strategies.

In response to this, some participants intervened in the discussion asking about the EU diminishing normative power, EU due diligence, and the impact of EUDR on developing countries exports.

The first question asked by Muhadi Sugiono, asks whether the EU’s actions, particularly with the EUDR and palm oil, show a decline in the EU’s normative power. Axel Marx highlighted that while the EU still recognizes itself as a normative force, its approach has moved from dialogue-based engagement to unilateral regulatory strategy. Instead of establishing agreements through negotiations, as in previous cooperation, the EU now employed market access as leverage to achieve its environmental objectives. This move is not necessarily motivated by self-interest but rather indicates a distinct approach to reaching global standards influenced by the Brussels Effect.

Another question, asked by Michael H Mercado, was how the EU’s due diligence process is implemented. Due diligence requires businesses to develop procedures that identify, prevent, and mitigate negative environmental impact in their supply chains. The most difficult component of the compliance of the due diligence is establishing full traceability, tracking commodities such as palm oil back to their source and making sure that they are not linked to deforestation.

Finally, the discussion addressed concerns about EUDR’s influence on developing countries’s exports. Mohammad Fajar Ikhsan argued that the regulation limits market access for commodities like palm oil, putting developing nations at a disadvantage. However, Axel Marx stressed that EUDR is not intended to be a protectionist instrument, but rather a compliance structure. Indonesia, for example, has already made steps to curb deforestation with regulations such as the 2011 moratorium. By following the EUDR, Indonesia may be able to expand its market access rather than being excluded.

The In-Europe Dialogue successfully fostered a meaningful conversation on a critical issue affecting EU-Indonesia relations.